We have talked at length about the lack of science to support many of the clinical reasoning models that guide orthopaedic physiotherapy and how they can cause fear in patients (ref). How often do we hear our patients recite what their previous clinician told them: My hips are out, my pelvis is twisted, my spine is degenerated, my muscles are full of trigger points? Ew. Why do these models persist? What purpose do they serve?

I’d argue that we are not unlike many of our patients in that we create narratives to make our world make sense. For example, patients often recall an event that may have happened years prior ("I played football in high school" or "I fell out of a tree when I was a kid") to explain why their back is now sore. Others recount an activity that they did a week before symptoms arose as the cause of their back pain. Now, in all likelihood, these events have nothing to do with why the patient is experiencing pain (albeit, they likely have something to do with why the pain persists; but it's a massive stretch to say they were the inciting event). But as human beings, we like our world to make sense and for there to be a cause and effect explanation for things. Why? Because a world with complex interactions that are beyond our comprehension is bloody scary. For a great review on patient narratives, check out this great discussion between Cory Blickenstaff and Erik Meira on the PT Podcast.

Healthcare professionals have created their own narratives for centuries. Take, for example, malaria – which literally translates from the Italian to “Bad air”. It was originally believed that the disease was the result of noxious vapors released from decomposing materials that were released in the night. The fix then, was to put up barriers to prevent this bad air from entering homes at night. This helped decrease the incidence of disease and so the model was believed to be correct for many years. It was not until the mid 19th century was it discovered that mosquitoes were found to be the mechanism by which the disease is spread. This is an obvious post hoc fallacy but the point is that these types of errors in our thinking likely still exist - we would be both arrogant and ignorant to think this will not happen in the present day. At some point, even some of our most infallible beliefs may be proven wrong for reasons and mechanisms beyond our present comprehension.

“ As much as we believe we are knowledgeable and cutting edge, there is every reason to think much of what is known now will be proven to be either only partially right or completely incorrect in the years to come.”

So why do we hold on to these models? As health care providers, we too are desperate for our world to make sense. Our schooling is competitive, they only choose the best and the brightest. We spend years in the class room learning anatomy, physiology, assessment, treatment etc. But where does it get us? If we are fortunate, it gives us a full understanding of the limits of our actual knowledge. Out of this is born an inconvenient truth: what we know now may very well be "Wrong" in 10 years and we really know very little about many of the conditions we treat. We can do our best to piece things together using the best possible evidence but there is always a strong possibility that there are unknown variables that interact in numerous ways that influence outcomes and we have no idea what they are. Think - we have no idea why most people experience low back pain and many of our interventions likely work for unknown reasons. 20 years ago it was believed that a specific mobilization would release meniscoid entrapment, stretch scar tissue etc. Now we think its effect may lay in neurophysiology and the central nervous system along with patient and clinician beliefs. Who knows where we will be in 20 years? As much as we believe we are knowledgeable and cutting edge, there is every reason to think much of what is known now will be proven to be either only partially right or completely incorrect in the years to come.

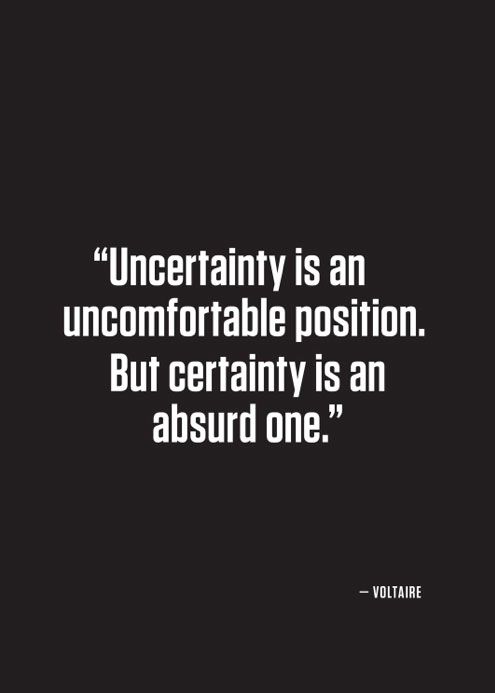

This knowledge causes "Clinical angst", or turmoil as we recognize that despite our best efforts, there is a realization that we simply cannot fully understand the totality of an individual’s clinical presentation and can never truly predict success with our interventions. But to acknowledge these facts leaves us in a position of uncertainty and creates great disquietude. This is one reason why alternative therapies that purport to treat all conditions are so appealing; they give a complete package that explains why someone hurts and how to treat it - the world makes sense. If the patient does not recover, the fault lies in the practicioners inability to apply the right treatment, not the treatment model. Treatments like myofacial release, visceral manipulation and subluxation based chiropractic come to mind when I think of this type of ideology. Often these interventions claim to treat a wide range of conditions, are presented with complex scientific explanations and little more than testimonials of miraculous success as evidence to support their usage.

So what can we do about this uncertainty on a day to day basis? Certainly using evidence as a starting point for decision making allows us to provide the treatment with a potentially higher likelihood of success. This must be tempered with the realization that not everyone will respond to a specific intervention and including clinical experience and patient values in decision making balances an over reliance on clinical trials. Regular retesting of impairments, pain and function allow us to determine if a patient is responding and change courses of action when there is a lack of response to treatment.

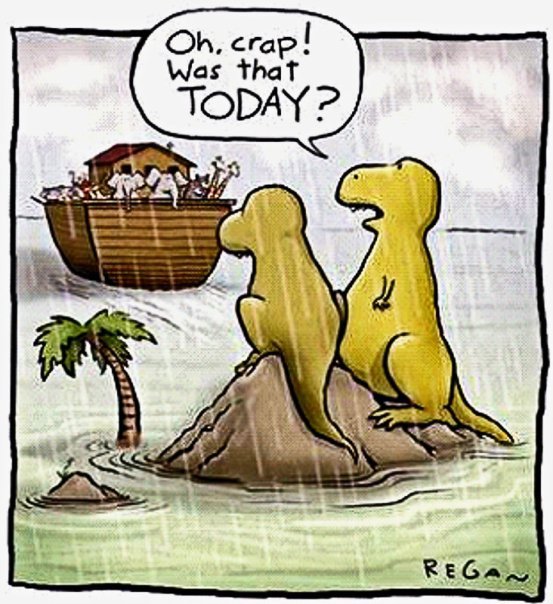

In the long term, we must realize that knowledge and evidence are moving targets and the status quo can never be accepted. This allows us to constantly adapt to emerging evidence and change within health care. Think critically about others ideas and practice patterns but be even more critical of yourself. Acknowledging your own biases and reflect upon your own practice patterns. Even more importantly, reflect on your interactions with patients as this is the true art of healthcare. Be sure not to marry yourself and create an emotional attachment to a specific treatment paradigm as it will be difficult to change your thinking when proven to be wrong. God forbid that you become a dinosaur!

In the long term, we must realize that knowledge and evidence are moving targets and the status quo can never be accepted. This allows us to constantly adapt to emerging evidence and change within health care. Think critically about others ideas and practice patterns but be even more critical of yourself. Acknowledging your own biases and reflect upon your own practice patterns. Even more importantly, reflect on your interactions with patients as this is the true art of healthcare. Be sure not to marry yourself and create an emotional attachment to a specific treatment paradigm as it will be difficult to change your thinking when proven to be wrong. God forbid that you become a dinosaur!

Feeling like you lack knowledge and are uncertain about what might be the most appropriate thing to do with the patient that stands before you? Get used to it. Strive to learn more but always think critically about what you learn and realize that there are few, if any, absolutes in the world of health care and golden bullets rarely exist. Ironically, learn not only to make better clinical decisions but also to realize how much you don’t know. The Dunning Kruger effect is a well studied phenomena where those individuals who have lower levels of knowledge tend to overestimate their expertise – put not so nicely – they are too stupid to realize they are stupid. Embrace change, whether it be in the type of treatment given or more often not, the reasoning for applying a particular treatment.

Feeling some self-doubt and a pang in the pit of your stomach? Probably means you are on the right track….

STEVE YOUNG, BSCPT, BA